Latency, bandwidth, and IBRL explained

TL;DR

- Latency is time-to-destination; bandwidth is throughput capacity

- From a client's perspective, bandwidth constraints often manifest as "latency"

- Inefficient client code can mimic network lag. We improved throughput by 400% just by optimising our SDKs

- Physical distance remains the ultimate hard limit on latency

- One of Triton’s (as well as Solana’s) missions is IBRL – increase bandwidth, reduce latency

- Triton is IBRLing through premium infrastructure, innovation, and open-source tooling (like the Yellowstone suite)

Why should you care?

This post breaks down latency and bandwidth in the context of real-time data streaming, and explains them in the way that matters most: how end users are affected.

When we talk about streaming, especially on high-performance blockchains like Solana, it’s easy to get stuck on server-side metrics. But systems are built to improve the human experience, and if the user perceives a delay, it means the system is slow.

To understand why, we have to look at latency and bandwidth not only as physical properties, but as experienced phenomena.

Latency vs bandwidth. What they are and are not.

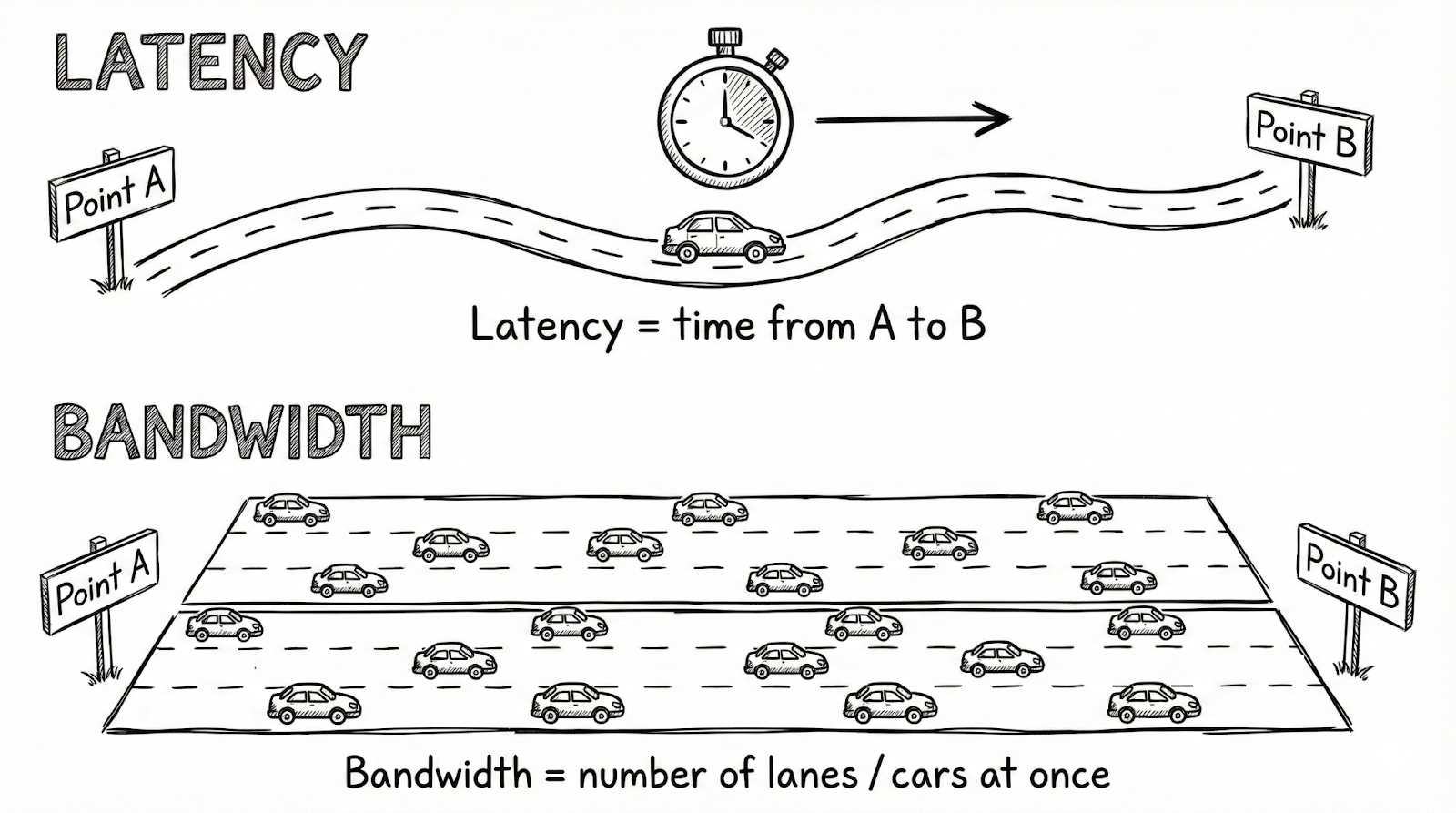

Classically, we define these terms as follows:

- Latency is the time it takes for data to reach its destination.

- Bandwidth is the maximum number of bits that can pass through a given path of wire at the same time.

The most common analogy is traffic on a road. Latency is the time it takes for a single car to travel from Point A to Point B. Bandwidth is the number of lanes, which limits how many cars can travel simultaneously.

However, this analogy fails to recognise the most critical piece of latency and bandwidth – perception.

👁️ The frame of reference

For latency and bandwidth to exist, they must be perceived. If you think it sounds awfully similar to Schrodinger’s cat – you’re absolutely right!

- You verify that data has arrived by checking for it at the destination.

- You verify that a wire has a specific bandwidth by measuring it in transit and at the destination.

Unless measured, these metrics don't effectively exist, showing that they should be considered from a specific frame of reference.

Because we build systems to improve the human (or developer) experience, this frame of reference is often the user’s perspective.

The UX serves as the anchor point in which latency and bandwidth are defined, making both metrics multifaceted because users not only interact with systems in different ways, but also receive data from different parts of the world.

End-to-end latency from Alice’s perspective

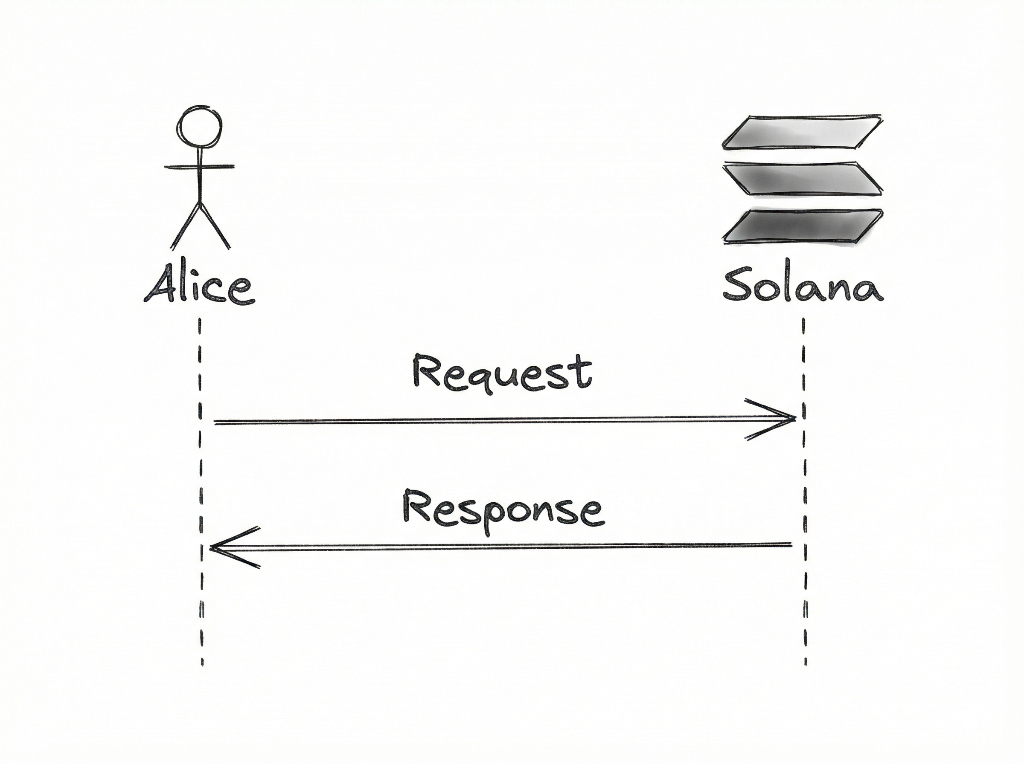

Let’s look at a practical example involving Alice. Alice wants to subscribe to on-chain Solana events using our yellowstone-grpc SDK.

When Alice opens a stream, she sends and receives data across a distributed network of machines. She does that by establishing a persistent connection (stream), rather than using the traditional request–response HTTP model.

However, for simplicity, we will use the analogy below to represent the lifetime of Alice’s request, and we’ll modify and expand this analogy as we go along.

Latency in Alice's eyes

If it takes 100ms for Alice’s request to be sent and 200ms for it to be received, then Alice’s perceived latency is cumulatively 300ms.

The bandwidth paradox

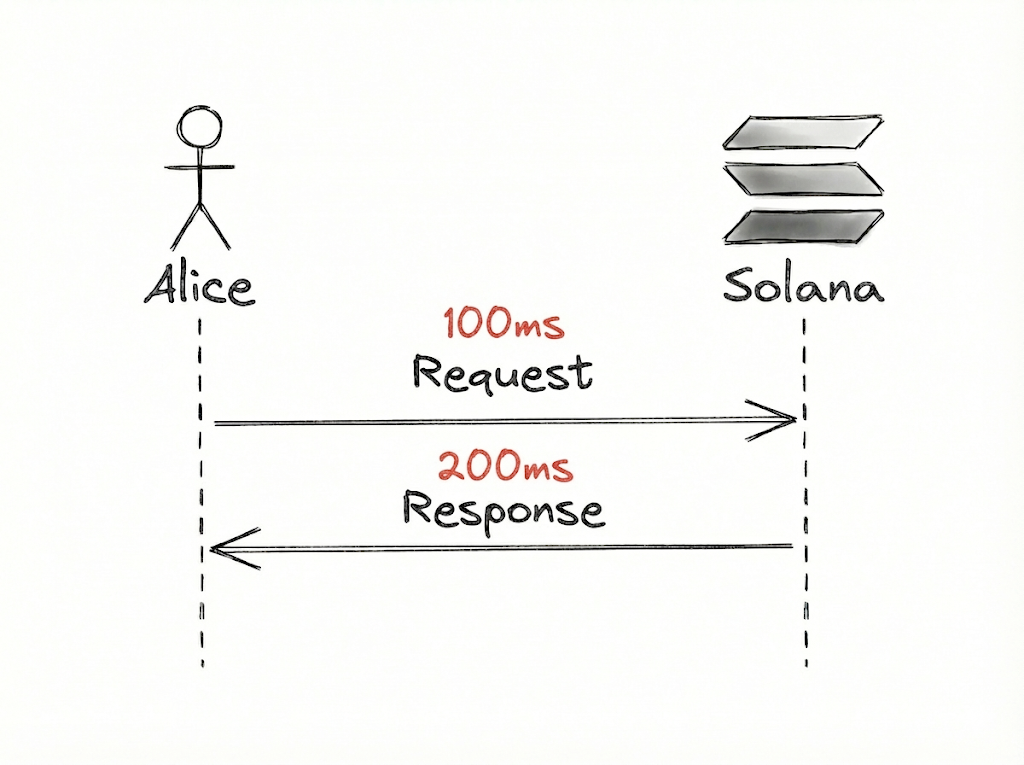

Bandwidth is trickier. For example, imagine the arrows in Alice’s and Solana’s diagrams are wires.

In our definition of bandwidth as the capacity of a particular network route to transfer data, we can double the bandwidth along the wire from Solana to Alice, reducing the time it takes for the complete response to reach Alice to 100ms.

This is because more data can be sent from Solana simultaneously.

Notice what happened?

We increased bandwidth, but from Alice’s point of view, we’ve reduced latency (from 300ms to 200ms cumulatively).

Without attaching complex profiling tools to the network interface, bandwidth is difficult for the end user to quantify. Fundamentally, from the client’s perspective, it’s just another parameter that influences the total time to result.

Hence, throughout this article, we will focus more on latency in a simplified and contextualised manner.

Simplified, but not simple: hidden latency factors

In reality, latency from Alice’s perspective is not just communication between her and Solana. For this data streaming to occur, there are numerous components and layers throughout its life cycle.

For example, before Alice can request data, her request must be prepared and a connection established.

Changing our diagram to the one below.

This allows us to see some parts wherein latency can be influenced from Alice’s side:

- Request ingestion from Alice

- Computation and request building

- Establishing a connection with the network

- Sending the request through the wire

Just by sending the request, latency can already be influenced by how requests are ingested, processed, and sent.

For example, we open-sourced a TypeScript SDK for gRPC streaming, and it became the default entry point for many teams because it lets you integrate Yellowstone quickly without writing Rust.

The trade-off is that Node.js is single-threaded, and heavy protobuf deserialisation in @grpc/grpc-js can block the event loop, trigger HTTP/2 backpressure, and slow ingestion.

As usage grew, we looked at end-to-end performance from the client’s perspective, meaning not only network travel time, but also client-side parsing, serialisation, scheduling, and backpressure.

We found overhead in the TypeScript client that capped throughput, so we rebuilt the core in Rust and exposed it through a JS interface as a drop-in replacement.

Result: 400% higher throughput (bandwidth), and a noticeably lower “latency” for users.

What else? Geography.

Another example is geographical constraints.

If Solana were Alice’s neighbour, the request-response life cycle would be rapid because the amount of wire Alice’s data and Solana’s data must travel is trivial.

However, imagine if Alice lives on Mars and Solana is on Earth.

The amount of wire Alice’s and Solana’s data must travel is astronomical (literally), therefore, introducing unavoidable physical latency into their communication. This highlights another layer that, from Alice’s point of view, affects the cumulative latency.

Both client-side bottlenecks and geographical constraints are just a few of the factors that influence latency in real-time data streaming.

But ultimately, both demonstrate the multifaceted nature of latency and bandwidth as metrics.

What’s next? IBRL: increase bandwidth, reduce latency.

Now that you have an understanding of latency, bandwidth, the user’s frame of reference, and examples of influencing parameters, it’s your turn to IBRL!

IBRL is one of the core missions of the Solana ecosystem and the Triton team.

We build the infrastructure and the open-source tools necessary to Increase Bandwidth and Reduce Latency for every user in the Solana ecosystem.

Whether it's improving our Yellowstone geyser plugin, optimising bare-metal hardware, or rewriting SDKs in Rust for maximum throughput, we are committed to making the data stream flow as fast as physics allows.